Please wait...

About This Project

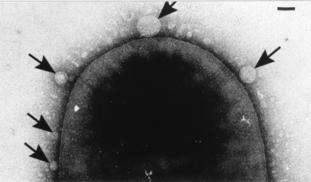

NU iGEM is creating a delivery system for an innovative antibiotic method centered around CRISPR, a powerful gene editing tool. With CRISPR, researchers can design guide RNA to direct the protein Cas9 to cut out any gene from a cell. In our case, we will target antibiotic resistance genes, leaving pathogens defenseless. We want to harness the natural messenger properties of bacterial outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) to package Cas9 and deliver it to cells as a biological Trojan Horse.

More Lab Notes From This Project

Browse Other Projects on Experiment

Related Projects

Highly-sensitive, real-time enzyme methane oxidation rate measurements using an electrochemical assay

A low-cost, rapid, and highly sensitive assay is needed to measure methane gas oxidation rates by methane...

Engineering of a suction cup stethoscope for non-invasive monitoring of physiological sounds in baleen whales

Baleen whales are large-bodied predators that, despite their critical role in marine ecosystems, our understanding...

Building a better fish: Engineering fish for smarter aquaculture

What if we built a better fish instead of depleting wild fisheries? Natural stocks can’t keep up with demand...