Abstract

Last summer, we used Experiment to fund our current research project on diversity and habitat use of eastern hognose snakes. Our research examines how and why these snakes on a barrier island are different from those that live on the mainland. Typically, hognose snakes measure about 3 – 4 ft. long, but all of the snakes we have found on nearby barrier islands have been under 2 ft. — a phenomenon known as insular dwarfism.

Really cool things happen on islands, and even today we don’t know what’s going on. It seems every animal has a different way of adapting to an island. We have a pretty good idea that hognose snakes that live on barrier islands are smaller, but we don’t really know why. No one does, so we’re going to try to figure it out. The first step in answering this question is gathering enough data to confirm that there is a significant size difference.

Introduction

The hognose snake isn’t like many snakes. It’s non-venomous to humans, minds its own business, and for the most part, has the potential to make a great pet (except for its specialized diet). But the most interesting characteristic about this snake isn’t its temperament, it’s the well-documented but puzzling defense mechanisms it displays.

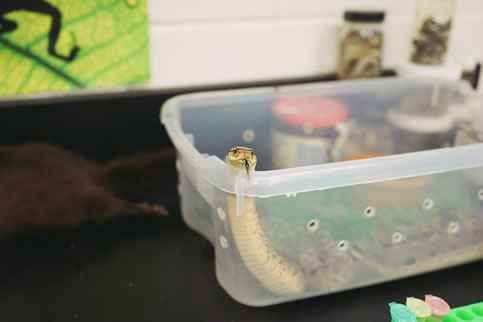

A female eastern hognose snake captured from a barrier island on Long Island, New York.

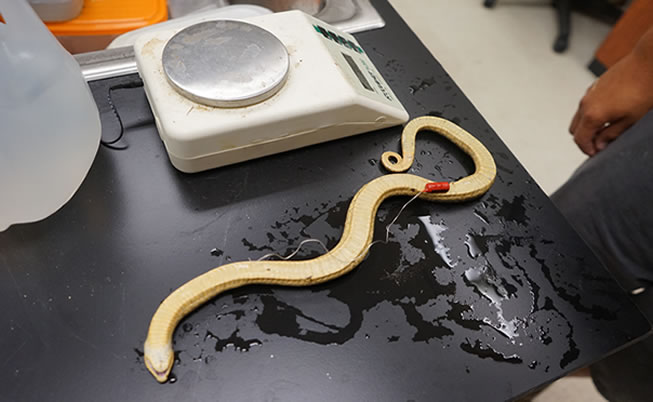

When threatened, the snake initially spreads its neck out like a cobra and hisses through tiny holes in its head. Because of this bluff, hognose snakes get killed by people more than any of other snake, even though they’re almost entirely harmless. But after a few short minutes of this, the snake starts writhing around in tightly coiled circles. Then, belly up and jaws open, it stops moving and goes completely limp.

The snakes are so committed to their craft that they can spend up to 20 minutes in this seemingly-lifeless state. You can do nearly anything to the snake, even stick a finger in its mouth, and it won’t snap back to reality.

A female eastern hognose demonstrates the snake’s unique defense mechanism of “playing dead."

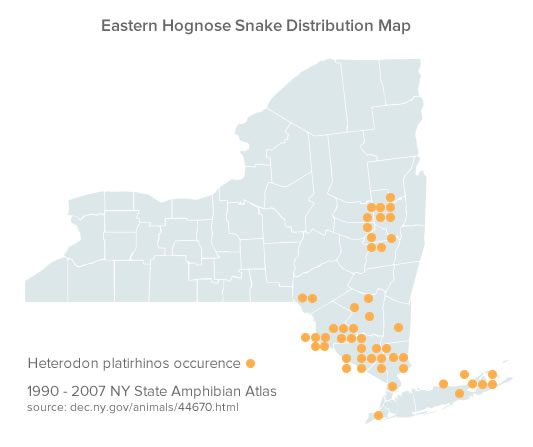

The eastern hognose snake is endemic to North America and can be found in areas ranging from eastern-central Minnesota, to the coasts of Florida, to southern New Hampshire. In particular, they inhabit barrier islands, a type of landform near coastal mainland that forms small inlets of water. These islands play an enormous role in mitigating ocean swells, creating unique ecological systems.

For this and many other reasons, hognose snakes make for a very unique study subject. There are so many unanswered questions about their behavior and the way that they interact with their environment. Our research is an effort to begin tackling these questions and increasing our understanding, little by little.

Methods

One of the most difficult aspects of studying snakes in the wild is that they’re so hard to find. They're great at hiding, and you can’t attract them or put lure out. So we use special wildlife tracking technology called radio telemetry to hunt down our study subjects

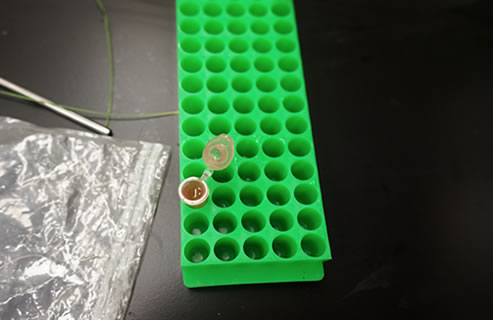

Once we've captured a snake from the wild, we surgically implant a tiny radio transmitter inside the snake's body. After it is released, we use a radio antenna and a receiver to locate the snake again. The antenna and receiver amplify the "beeps" that are emitted from the transmitter, so as we approach the snake, the receiver will beep louder and more frequently.

But before we can outfit a snake with a radio transmitter, we need to first find snakes in the wild. It is rare that we will find a snake just by stumbling across it. So initially, we must find snakes by setting up homemade snake traps. The traps have a fence that the snakes run up against as they cross between the dunes. As they move along the fence looking for an exit, they end up in an enclosure that is difficult for the snakes to get out of.

A handheld radio receiver and antenna helps locate snakes that have been equipped with transmitters.

A homemade snake trap is used to capture snakes for study.

Fences around snake nests keep predators from digging up the eggs for a meal.

In the Lab

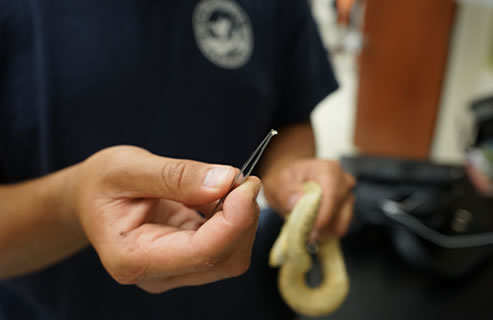

After capturing a wild snake, and before it receives transmitter surgery, we take the snake back to the lab to record information about it — it’s length, sex, weight. Then, we use a small pair of sharp scissors to take a scale clip (like clipping a fingernail) that we put in a small vile of ethanol to preserve for DNA analysis.

Next, we’ll take a photo of the head of the snake, and draw the pattern we see. No two snakes have the same head pattern, so this helps us identify and distinguish between the various individuals we take in.

After we collect this data, the snake is taken to the veterinarians at the Bronx Zoo for transmitter surgery. Once the snake's sutures have healed, it is ready to be released back into the wild, where we will track and record various information about its behavior and habitat use.

Using scissors to take a small scale clipping used for DNA analysis. This does not hurt the snake.

The transmitter is surgically implanted into the snake, and runs along the length of its body.

Holding the heads of two Eastern Hognose Snakes side by side shows that each snake's head pattern is unique.

We raised only $1,100 on Experiment, but it was enough to kickstart our project from no money and no data, to a full-fledged research operation. The first five transmitters for this project came from money we raised on Experiment, and because we had success with those first transmitters, we were able to use that preliminary data to get a grant to get more transmitters. Grant agencies need to see that you know what you’re doing, so it really snowballs.

Now, we have eight snakes in the wild equipped with transmitters (8 last year and 8 this year), and we have collected data on over 65 individual snakes on the barrier island. We’re currently awaiting DNA analysis to return from a genetics lab, which we’ll use to compare genetic diversity among populations.

Scale clippings are sent to a genetics lab for DNA analysis. This will tell us more about the snakes' evolutionary diversity.

Results

After over a year's worth of research, we have collected data on 65 unique samples of eastern hognose snake

We set out to learn more about the size difference between hognose snakes on islands vs. the mainland, and our research adds supporting evidence to the idea that eastern hognose snakes experience insular dwarfism.

The sizes of snakes we studied on Long Island and a barrier beach of Long Island were found to be smaller than previously recorded sizes of snakes on mainland areas (Fig. 1 ).

In addition to data on snake size, we also gathered corollary data about the eastern hognose snake's use of habitat on a barrier beach.

Data points on Fig. 2 represent various ways that the snakes use their environment. "Hibernacula" are locations where the snakes dig down into the sand to hibernate for the winter. "Initial encounters" mark spots where the snakes were first discovered, before tracking began. "Relocations" are where the snakes were later found using telemetry. "Tracks" are where the snake left behind a visible trail in the sand or shedded skin.

Using radio telemetry data, we were able to estimate the home range of 9 different snakes (Fig. 3 ). Ranges are visualized by drawing a line around the furthest points, called a minimum convex polygon.

Fig 2. Snake Landscape Use

Fig 3. The estimated home ranges of nine different snakes.

Conclusion

The results of our research are a big step forward in our understanding of the eastern hognose snake. Prior to this study, very little information had been recorded about eastern hognose snakes on islands. Our findings create a stronger case for insular dwarfism, but they also surface a ton of new, interesting questions.

We found that eastern hognose snakes on Long Island and a barrier beach in New York are smaller than eastern hognose snakes that inhabit the mainland. This adds to a growing body of evidence that many species experience “insular dwarfism,” or reduction in size over generations due to limited environment.

We have yet to understand why this phenomenon occurs. But this research will, over time, help us fill in the blanks about why “the island rule” occurs in some species and not others. Ultimately, this lends to a more complete understanding of evolution.

Future directions for this research might examine specific questions related to why snakes are smaller on a barrier island. Was it a result of a small founder to the island? Evolution to a small food source? Pressure from predators?

Data we collected on the snake's habitat use also raise some new questions: Why are eastern hognose snakes the only species to live in the dunes in this area, whereas on other islands, there are many other dune snakes (even on Long Island)? Why are they so abundant in the dunes? Hognose snakes are usually considered rare.

We are hopeful that our data will get published in one of the reptile and amphibian journals, or even a bigger journal like The Journal of Biogeography or Landscape Ecology.

When I started this Master’s, we didn’t know the population was so large. We didn’t know they would all be uniform in appearance. We also didn’t know where they live; I found this study site on my own. All these things will help me in the future as a wildlife biologist. It shows that patience, good field work, and knowing the natural history of your study organism pays off.

John Vanek1

John Vanek1