Please wait...

About This Project

The Precautionary Group

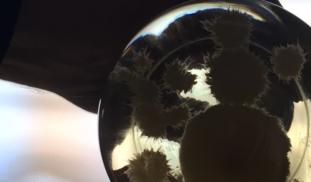

We've discovered a few new mushrooms thriving in this harsh environment of land-disposed sewage sludge in Snoqualmie, Washington. We're testing these mushrooms for new antimicrobial properties. Microbes that survive exposure to toxic sewage sludge engage adaptive mechanisms that transform toxins into secondary metabolites.

More Lab Notes From This Project

Browse Other Projects on Experiment

Related Projects

Disrupting cancer cell signaling through drug discovery

Most cancer-related deaths are caused by metastasis, the spread of cancer cells to distant tissues. This...

CaniSense– AI-powered blood test for early cancer detection in dogs

Cancer is the leading cause of death in dogs, yet no reliable methods for early screening exist. At testblu...

Shutting down cancer’s recycling system with exosome-based therapy

Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest cancers because its cells survive by recycling their own components...