Abstract

Beer brewers can use malted barley as a source of naturally-occurring bacteria in the production of sour wort. This experiment is designed to assess the variation of bacteria found in malted barley across variables including harvest year, varietal, origin, and processing. The results show there is much in common between bacteria found in malted barley and resulting organic acid and alcohol production regardless of variables.

Introduction

Sour beers are likely the original beer style and have made a recent comeback in terms of popularity among craft beer enthusiasts. They are made with a bacterial and fungal mix rather than pure cultures of Saccharomyces. yeast as in typical ales and lagers. However, the suite of different microbes and their relative abundances during the course of souring and fermentation remain a mystery. We aim to map part of the sour beer microbiome (specifically wort souring bacteria found in grain) and identify the organic acids these microbes produce.

Methods

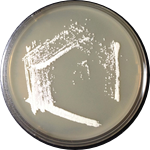

The object of this experiment is to determine the microflora on various malted grains and to sample souring beer at various time points to determine which microbes thrive, grow, and ferment during wort-souring. Blue Owl Brewing will collect the samples over the course of 24 h. The Bochman lab at Indiana University will then isolate microbial DNA and prepare next-generation sequencing libraries. The DNAs will be sequenced and the samples compared to one another to: 1) determine the species present and their relative abundances at each time point; and 2) how that microbial community changes with time. The organic acids in the final beer (lactic acid, acetic acid, etc.) will also be identified, as these are the compounds that the tongue recognizes as "sour".

Sample Preparation Lab Notes:

https://experiment.com/u/nTqd6...

Results

Below are links to interactive charts showing various comparisons of the results of rDNA sequencing of bacteria found on malted barley and in wort inoculated with the malted barley. Additionally, there are charts showing the resulting organic acid profile and alcohol production of the soured worts.

The "NRBS" (nutrient-rich buffered starter) contains a sample preparation of wort that is spiked with a ground sample of malted barley. The t=0 represents the sequencing of bacteria collected immediately after the malted barley is mixed into the wort. It can be expected that this sample most accurately represents what bacteria is naturally found on the grain before any growth.

After the NRBS is inoculated with the malted barley and incubated at 110F for 24 hours, a portion is used to inoculate fresh wort at 110F (representing wort in sour-wort production). The NRBS t=24hrs and Sour Wort t=0 have essentially the same bacteria composition and is not shown here.

The Sour Wort samples are then compared across the various malted barley inoculants used at time points t=0, 24, and 48 hrs (not all samples have all time points). Comparisons can be made between different harvest years, different incubation times, different varietals, and different origins.

Lastly, a quantitative NMR analysis shows samples collected from the Sour Wort samples at time points t=0, 24, and 48 hrs (not all samples have all time points). Comparisons can be made between different harvest years, different incubation times, different varietals, and different origins.

Sequencing NRBS t=0

Sequencing Sour Wort t=0

Sequencing Sour Wort t=24

Sequencing Sour Wort t=48

Sequencing Sour Wort 2015 vs 2016 Briess Merit 57

NMR Organic Acid Profile

NMR Alcohol Production

Conclusion

This experiment was set up to test a wide variety of malted barley samples in the hopes that some common characteristics could be found. Trying to use a wild culture like the bacteria found on and in malted barley for the purposes of souring wort in sour beer production can be a daunting and frustrating task. Being able to control the production variables can be difficult enough, but if the souring bacteria cannot be "tamed" and batch-to-batch variations are too great, large-scale production of wort-soured beers could be unfeasible.

Fortunately, there seems to be a few things a brewer can count on when using a variety of malted barleys for inoculation. At the temperature used for incubation in this study, there was a fairly consistent and dominant bacteria strain found in the sour wort--regardless of the medley of bacteria found on the grain--and that's Weissella cibaria. We actually were expecting the sour worts to be dominated by the "usual suspects" used in kettle souring, lactobacillus strains like L. brevis or L. plantarum. There was one sample, however, that was dominated by a few lactobacillus strains (W. cibaria was still dominant in the sample at t=0 and to a lesser degree at t=24hr) and that was the 2016 Briess Merit 57, t=24 hours. It is not understood why this particular sample was different from all of the rest.

Since Weisella cibaria was the dominant souring microbe in the majority of the samples, brewers can use the characteristics known of this species to help properly conduct wort-souring using grain at this temperature.

Another interesting result of this study is the variety of organic acids and alcohols produced during the growth and metabolism of the souring microbes. All of the samples had lactic acid being the dominant acid (as expected), but additionally acetic acid was present between 13.8% and 24.4% of total organic acids found. Succinic acid was found in all samples and was produced up to 3.3% total organic acids. Also found in nearly all samples were malic acid and pyruvic acid.

Perhaps one of the strangest findings in this study is the comparatively high amount of ethanol production in the 2016 barleys compared to the 2015 harvest year samples (with the exception of the Blacklands Malt). The 2015 samples produced typically around 0.15% ethanol v/v, but the 2016 samples produced at least 0.9% and the 2016 Briess Synergy sample producing nearly 2.5% ethanol v/v in 48hrs.

Lactic acid production was surprisingly similar throughout all the samples with the exception of the higher concentration in the 2016 Briess Synergy sample. This characteristic of the dominant bacteria is rather convenient for sour-wort producing breweries since a consistent acidity level (and resulting sourness level) can be achieved or possibly controlled more or less with time.

All the results combined show that using this method of wort-souring from bacteria naturally found on malted barley can both produce a controllable, fairly consistent resulting beer with a complex profile of organic acid and alcohols.

More studies need to be conducted to explore variability, but also to explore variations in brewing process control, most specifically incubation at different temperatures. Weisella cibaria is seen to be dominant at 110F, but it is also known to not thrive above 113F. If a brewer was to produce sour wort lower 110F or higher than 113F, it could be expected that other bacteria with other attributes may dominate and change the character of the sour wort.

Matthew L. Bochman1

Matthew L. Bochman1 Jeff Young2

Jeff Young2